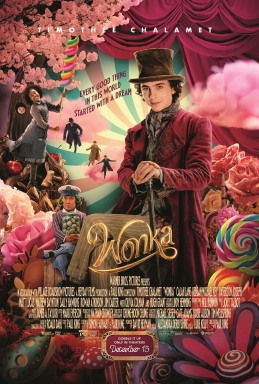

The recent movie, Wonka (2023), tells us the origin story of Willie Wonka, the owner of the chocolate factory from Roald Dahl’s novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Since it is a movie for children, it also showcases, with straightforward clarity, some of our taken-for-granted assumptions about work, slavery and sales, i.e. our capitalistic imaginary.

The movie takes place in a non-descripted town and age. The town is European, maybe London, maybe Paris, no landmarks, just cute shopping streets and passages (a la Walter Benjamin). Age? late 19th century, early 20th century. They have cars and phones, both vintage by our standards.

The movie follows Wonka’s descent into this unnamed city as he tries to make it into the world of business. The modern hero wants to open a chocolate shop on the most famous commercial street in town. He wants this because his mother told him about this amazing street in this city where the best chocolate grows. Wonka has emotional ties to chocolate, he wants to make and sell the best one in the world, like the one his mom used to make. Many kids want to have odd jobs when they are little, but then they grow out of it. Wonka kept the childhood dream with obstinate desire. It was the only thing that kept his mom’s memory alive. Thus far, we can resonate with him, as audiences watching on the edge of our seats. But as he tries to make it as a chocolate business owner, things get strange.

On his first day in town, Wonka puts himself into slavery. He signs a contract without reading the fine-print, and suddenly he is in debt, owing thousands of sovereigns to the lady who hosted him for one night in her inn. Because this is how capitalism works, slavery is legit. Although, in the 19th century, it was. People went to prison for being in debt.

The inn-lady owns a clothes-washing business and Wonka gets sent to the basement to wash clothes with other forced laborers: an accountant, two women, a failed comedian, and a child called Noodle. All these adults take it for granted that a contract is sacred and their signature binds them to life to a debt caused by overpriced items that they seem to have consumed. Even using the air in the room rented for the night, drinking a glass of gin offered seemingly of hospitality, using the bed linen, everything is infinitely expensive. All these people were grown ups (except for Noodle who got there by being abandoned, so she never signed a contract) accept their fate to slave away for lending money that they never received. The value of one room in an inn for a night is infinite if the owner decides so.

In the present world, such contracts would be void since these go against the laws of most states. In the fictional world, contracts are binding and it is more important to try to work for the contract duration rather than escape or run away, even if it means decades of slavery in a basement. Compare this situation with Oliver Twist, the novel by Charles Dickens. A band of thugs force children, including Oliver, to steal and beg in the streets of London. The children are exploited and hate their life. Abuse is called abuse and nobody makes it about honor or contracts or even friendship. The children stay in the beggar’s ring because they cannot escape, they are prisoners and they know it. Meanwhile, Wonka and his friends stay because they want to sell chocolates in that particular town. Also because abiding by a contract seems to be the highest duty in this fictional city. They escape quickly out of the basement by devising an ingenious plan to make the dog work for them. They are free to roam the town, but they don’t, they go out to work for Wonka. They were forced prisoners for the lady of the inn, but they work for Wonka for free, out of friendship. Nothing is said about profits or salary. Or labor. Wonka makes the chocolates he sells at night, through magic. Just that, magic. The capitalism is all about selling in this movie, while labor is erased, not just invisible, but non-existent. Chocolates simply appear in Wonka’s hands and the main issue is how to sell them. Wonka’s capitalism is frictionless, painless, just sales. the inn-lady who has a clothes washing business represents the ugly capitalism, the one that forces you to work for no wage, in pain and steam, until you die in a basement.

It’s a movie about friendship but we are never shown what Wonka does for his friends. Until the end, they help him and rescue him, while he exploits them with a smiling face. In corporations, new public management is about making the employees feel like a family. They work happily, out of sheer commitment to the company, with salary being just a side-bonus. Wonka is a likeable guy, and this seems enough to have people befriend him and work for him. For free.. What a strange movie. If people will watch it over a century, they will be surprised with how much we loved sales, capitalism, and exploitation. All in the name of friendship. Friendship is magic, but it does not right all the wrongs.

Leave a Reply